🇺🇸 Uncommon, unsettled, unresolved

I went to New York City looking for answers and all I got was a brand new bunch of questions to mull over and over and over and over and over and over and over

I went to New York City last week looking for answers.

If you’d asked me whether that’s what I was doing at the time, I’d have flatly denied it. But on reflection, I think I’d unwittingly slipped into that mindset. It’s easy to fall into the habit of seeking clarity—the next insight, the next practice, the next big shiny idea.

I arrived in the US with the quiet hope that I’d come back with something concrete. A few hot takes and a sharper sense of how to do this work better. I was hoping to find something that would punch through the fog and force everything into focus.

And I did discover some new ideas. We saw some remarkably thoughtful practice. We experienced moments that delighted, moved and inspired us. But what I found more of—and what I haven’t been able to shake since returning—were questions. Beautifully unsettling, necessary questions.

That’s interesting to me because we definitely weren’t searching for silver bullets. We went to NYC to uncover what sits beneath the surface of the routines, rituals and decisions that shape what young people experience in a handful of excellent schools. This much is true.

What the visits surfaced for me, however, were some assumptions I’ve been holding—assumptions about teaching, leadership, and belonging—that I need to re-examine.

And, this week, like a rising sun burning off the morning fog, those questions have begun to reveal the shape of the landscape beneath. Not with immediate clarity, but with enough definition to show where I might need to look next.

So, this isn’t a tidy write-up. It’s a set of questions and meditations that I am happy to share and sit with for a little longer.

🏋 Joy through rigour

At The Reach Foundation, we often talk about the dream school as one that delivers a heady blend of rigour and joy. I know we’re not alone in this.

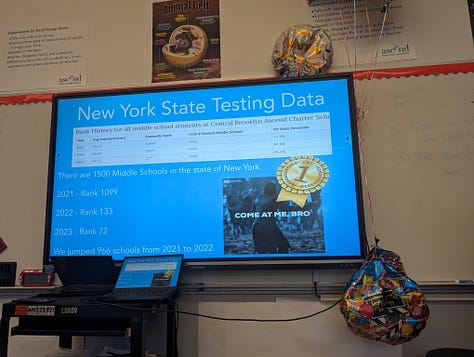

During a visit to Central Brooklyn Ascend Middle School last year, we met a former marine-turned-principal who talked about building a “disciplined funcastle.” He wanted his school to provide the discipline of the US Marines Corps and the joy of a bouncycastle.

It’s a glorious mental image, right? Rigour and joy, side by side, and they have the receipts to prove their approach is working (☝️).

But at Vailsburg Elementary School in Newark, the paradigm was slightly different—and it made me pause.

We started the morning in ‘circle time,’ where grades 3 and 4 gathered in a gym for a daily ritual. It was loud, joyful, choreographed, and full of energy.

Jon’s live commentary captured the vibe perfectly (as per, Jon is very good at this):

But it was also rigorous.

We watched children hold extraordinary cognitive loads in their heads during 15 minutes of mental maths drills. And the kids didn’t just get the answers right—they explained their thinking. They narrated the strategies they’d used, justified why one was more efficient than another, and did it all in front of 150 peers. No opt-out, no drama. There was zero sniggering. The sight of these primary-aged children championing one another was glorious.

Later, during a Q&A with the group, Valisburg’s elementary principal, Mariah Copeland, referred to the circle as “my classroom.” She referenced how aware she was of—and how grateful she was for—the opportunity to model oracy, curiosity, and confidence to sections of her school community every day. It was a performance, sure, but a considered one full of purpose and intent.

And it wasn’t just for the children. It was great CPD for the adults too.

And it made me wonder… how, back home, we often we use assemblies to “free staff up” to get other (important) things done.

But what if we’ve misunderstood their potential? What if those shared moments are one of our most underused learning tools (for students and staff alike)?

What would it mean to reframe existing communal school rituals (like assemblies) as high-quality professional learning opportunities?

The ‘circle experience’ also revealed to me the extent to which I have inadvertently internalised the idea that ‘joy’ and ‘rigour’ are independent. Joy—and belonging—is created by doing hard things together. Somewhat embarrassingly, I think I had forgotten that—and I was grateful to have it reaffirmed.

🥛 ‘Blue top’ instructional leadership

During a rare quiet moment on the bus back from Newark, something fell into place for me.

I’ve spent years thinking about instructional leadership. I’ve experienced it, embraced it, advocated for it, been frustrated by it, and even rejected it at various points in my own career to date. I’ve enjoyed moments when the focus sharpens, when the conversations deepen, when the leadership of teaching feels like the core of the job rather than the thing squeezed in between everything else.

But what we saw at Uncommon Schools wasn’t that. It wasn’t instructional leadership as garnish. It was the full-fat version. Blue top. Uncompromising. Immersive.

Mariah wasn’t dipping into lessons for a walkaround before retreating back to an office full of emails. Her days are steeped in teaching and learning. Her daily beat is bent around coaching, modelling, and feedback. The mechanics of great teaching aren’t delegated—they are led.

And crucially, she isn’t trying to do this as well as everything else. Because she doesn’t do everything else.

Enter the Director of Operations: a role so quietly transformative that I think it deserves much more attention. At Uncommon Schools, as is increasingly common across many charter schools, designated ops leads hold the rest—the logistics, the scheduling, the parent comms, the paper cuts of daily school life—so that instructional leaders can focus on, well, instruction.

I think this is way more than a staffing tweak. Which made me wonder:

Is full-fat instructional leadership rarer in our system? If so, why?

What might we need to let go of—structurally, culturally, personally—to reclaim the bit of the job we routinely say matters most?

💥 What if we challenged the frame—and deliberately made things messier?

At KIPP Beyond, we met Joe Negron, a principal who co-founded and led KIPP Infinity, one of the network’s highest-performing schools. Infinity was known for its tight culture: high expectations, high structure, high control. It worked.

Joe could have stayed the course. But he began to question the frame. He wondered whether there might be other ways to get to the same outcomes—ways that gave children more ownership, more autonomy, more humanity.

At KIPP Beyond, the culture is intentionally looser. It’s not lax, but it is relational. Critically, it is a choice. It’s looser by design rather than by default. Students are trusted. Staff are asked to operate with context and compassion. There’s a tolerance for ambiguity and for things not being perfect.

Joe was honest with us: “Would kids learn more in a more structured environment? Probably. But would I trade it? No.”

“Is this approach harder for us (adults)? Does it demand more of expert teachers? Yep, it does.”

What struck me most about Joe was his clarity and humility. This wasn’t an abdication of standards. It was a deliberate and explicit intention to find a different route to the same destination—one that values trust over control, development over compliance, relationships over rules. He also had a great sense of humour.

And it made me wonder:

Am I (are we) too quick to read order as safety—and mess as risk?

To what extent do I truly believe that children can flourish in messier environments without rigid compliance?

What would it take to lead like this in our own system?

So, unsettled and unresolved—but in a good way!

I came to New York looking for insight. I found something harder to hold: tension. Questions I don’t yet know how to answer. Assumptions I hadn’t realised I held. But maybe that’s the point of learning. Maybe we don’t always need a conclusion. Maybe we need to let the questions do their work to burn the fog away first.