The problem with Brutalism, Brasília and blueprints

Schools are complex systems—let’s stop managing them like machines

I am a millennial with a deep, enduring affection for mid-century modernist design. It’s a cliché. I’m embarrassed about that. But it’s the truth.

With its clean lines, functional elegance and, crucially, the conviction that good design can shape human behaviour for the better—it’s a design philosophy that’s intrigued me for as long as I can remember.

But I’ve also come to appreciate its flaws. Domestically, my still-small children have laid waste to any aspirations I might have harboured towards an intentional, neat and coherent aesthetic. It’s been humbling.

Architecturally, one of the grandest ideas of the mid-century period was that we could design cities from first principles and that, with the right blueprint, we could engineer better, more efficient ways of living. The Brutalist movement, in particular, emerged from this mindset: bold, ambitious structures designed with a clear vision of how people should move through and interact with space. And yet, many of these cities and buildings, despite their aesthetic and intellectual ambition, failed to function as intended.

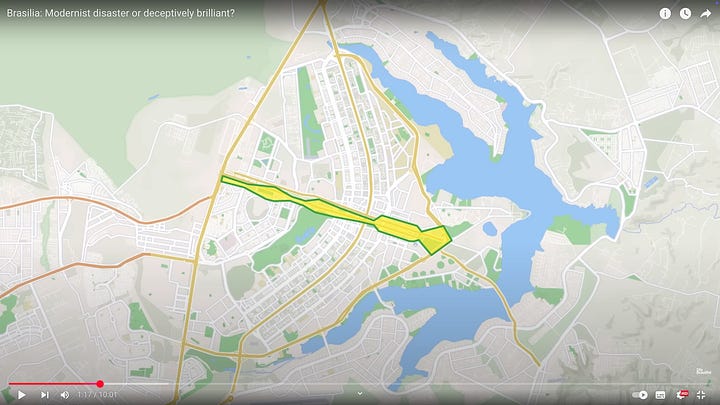

Take Brasília, the capital of Brazil. A city designed almost entirely from scratch in the late 1950s. The planners envisioned a masterpiece of order and efficiency—wide-open spaces, sweeping boulevards, and neatly divided zones for living, working, and leisure. It was a city built to be logical.

🔗

But, quite wonderfully, people don’t always behave logically.

Despite their design brilliance, critics assert that many new communities, towns and cities created in this image feel lifeless. Or, at least, they lack the organic messiness—the human-scale complexity—that makes towns and cities feel lively. Planned cities that don’t quite work in practice.

By contrast, cities that have evolved organically over centuries—London, Tokyo, Barcelona—tend to be messier and more responsive to the real needs of the people who inhabit them. They weren’t built from a single masterplan; they’ve emerged through countless small, local decisions.

What does this have to do with schools?

I would argue that we have, quite sensibly, tried to design school systems the way planners designed cities like Brasília.

We’ve created structures and systems that make sense on paper; assuming that the right blueprint will yield better schools so long as the model is implemented with fidelity. But schools, like cities, are complex, adaptive systems. They are not predictable machines but living ecosystems, full of human interactions, feedback loops, and emergent behaviours that can’t be controlled from the centre.

If we take one lesson from urban planning, it’s that systems designed for efficiency struggle in practice when they don’t account for complexity. This is not just a problem in city planning—it’s a problem faced in all sorts of domains, including education. If we recognise that schools function more like evolving cities than engineered machines, it follows that the way we lead and manage them must change.

This article is the first in a three-part series exploring that idea. Over the next few weeks, I want to explore:

🔴 What complexity science tells us about how schools actually work,

🟠 Why traditional trust leadership models don’t fit the reality of schools, and

🟡 How we might rethink trust leadership to align with complexity rather than fight against it.

Without further ado, let’s dive into the first of those…

🔴 What makes education complex?

A complex system is one where many interdependent parts interact in ways that create unpredictable, emergent outcomes. Unlike complicated systems (which may be difficult but remain predictable, like a car engine or an Excel formula), complex systems have no single point of control—they evolve through interaction, feedback loops, and adaptation.

We encounter complex systems everywhere:

Ecosystems are complex systems—a small shift in temperature can lead to cascading effects across entire food chains.

Cities are complex systems—the placement of a new train station can unexpectedly reshape a neighbourhood’s local economy.

Human brains are complex systems—billions of neurons interact dynamically, forming new pathways in response to different experiences.

Education shares many of the same characteristics—except unlike ecosystems, cities, and neural networks, we often try to manage schools as if they were predictable machines.

Here’s what complexity looks like in education, with some specific, real-world examples:

1️⃣ Interconnected agents: No school is an island

Schools don’t operate in isolation. Every school in the country is deeply embedded in overlapping systems—including students, teachers, school leaders, governors; Other local schools; Trust executives and trustees; Families and communities; Local authorities, social services, physical and mental health providers; National policymakers, Ofsted and the DfE.

Each of these agents influences and reacts to the others. A small change in one part of the system can send ripple effects across the whole network. For example, a marginal year-on-year increase in students with EHCPs might seem like an isolated statistic. But in reality, it can:

Shift the entire funding model for a school, forcing trade-offs elsewhere;

Reshape classroom dynamics, requiring new pedagogies and approaches to behaviour management; and,

Increase strain on local SEND services which, in turn, affects waiting times for diagnoses.

At no point did a single decision-maker create these outcomes—they emerged from interactions within the system.

2️⃣ Adaptation and feedback loops: Schools are dynamic

Schools are like stock markets (wait, hear me out!) in the extent to which the sands they stand on are constantly shifting—agents have to adapt dynamically to new information all of the time. It never ‘sets.’

For instance, if word gets out that the Bank of England is going to increase interest rates in a bid to reduce inflation; economists will reasonably expect domestic consumer and business spending to fall (as the cost of borrowing goes up) and for stock prices to fall as a result of this reduced commercial activity. If national economies were totally isolated from one another, we could be pretty confident that this would happen. But they’re not. National economies are interdependent. Global economic trends, politics and human psychology interact—making it impossible to predict movements with certainty.

When it comes to investing in stocks and shares, there is no single ‘best practice’—only ongoing adaptation.

The same is true in schools. For example, if a trust introduces a new primary maths scheme—an evidence-informed decision based on oodles of research—it could feasibly lead to improved outcomes in School A and worse outcomes in School B. Why? Because context matters. Perhaps School B has more EAL learners or reading comprehension is just marginally lower in School B. This marginal difference might render the more abstract language used in the maths scheme inaccessible for some children.

We’ve all seen this scenario before. We know that the most effective schools and teachers will use this feedback to flex—they’ll adapt their delivery. The most effective trusts will adapt the model to further support flexible implementation in different contexts. This process is annoying for everyone involved because we crave a sense of completion. We’re desperate to finish the job. This bit of the work is fiddly, time-consuming, and intellectually demanding—but it’s necessary.

3️⃣ Emergent outcomes: Schools are more than the sum of their parts

Karoline Wiesner, Professor of Complexity Science at the University of Potsdam, describes emergence as the phenomenon where a system exhibits properties or behaviours that its individual components do not possess.

The internet exemplifies this quality. The internet we know today hasn’t been created by a central authority. Sure, the ARPANET was created by the US Department of Defense but it’s evolved a fair bit since then—through trillions and trillions of high-frequency, widely distributed, unplanned interactions every single day. The algorithms that power it adapt in real-time; networks of users shape trends and information flows unpredictably.

No one designed it as it exists today—it emerged.

What of education?

To what extent do schools exhibit properties or behaviours that their individual components do not possess?

‘School culture’ is a good example of an emergent property. No single teacher, student, or leader is the culture of a school. Yet, over time, through thousands of daily interactions—classroom norms, assemblies, conversations in corridors, parent engagement, sports days—a distinct school culture emerges.

Two schools within the same trust, with identical policies and structures, can still feel fundamentally different because culture isn’t designed from the top—it emerges from interactions.

For my money, this is the most interesting aspect of complex systems. The most effective schools develop unique cultures, traditions, and solutions that couldn’t have been planned in advance. When we think about the biggest leaps in the profession in recent years, where have they come from? Were they pushed from the centre? Or did they emerge from the ground?

In all honesty, I don’t know the answer to those questions. But I think it’s fair to say that many now widely adopted teaching strategies (do nows, no opt out, positive framing, metacognition, etc.) didn’t start as national policies—they emerged from professional practice and later became codified and scaled out.

Emergence in schools means that trust leaders can influence outcomes, but they cannot fully predict or control them. Instead of rigidly enforcing policies and expecting uniform results, trust leaders should be attuned to emergence—identifying what’s working, amplifying positive patterns, and adapting as new realities emerge.

If we accept that schools, like the internet, are dynamic and self-organising, then trying to manage them with static, top-down control might temporarily improve their efficiency but will reduce their effectiveness in the long run.

4️⃣ Resistance to over-standardisation: Options trump obligations

Complex systems thrive on variation. What works there might work here—but it’s never as simple as ‘drag-and-drop.’ Crucially, the decision-maker—the person who decides whether or not a standardised element is adopted, adapted or rejected—should be the agent closest to the issue. In education, sometimes that’s a teaching assistant; sometimes it’s the trust executive.

When done well, standardisation provides two key benefits to a system: it improves quality (primary benefit) and frees up capacity for other priorities (secondary benefit). Whatever we standardise—whether it’s a curriculum framework, an assessment model, or a behaviour policy—it should be something that’s worth doing well, consistently, so that time, energy, and headspace can be directed elsewhere. The key is knowing what to standardise and what to leave flexible.

Standardisation should never be about imposing uniformity for its own sake—it should be about eliminating unnecessary variation in areas where consistency adds real value, while preserving adaptability where local judgment matters. Fundamentally, it’s about acknowledging opportunity cost and accepting trade-offs: every decision to lock something in at the system level means trading away the ability to adapt at the local level.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s said that countries that used adaptive, localised responses (like Taiwan and South Korea) fared better than those that relied on rigid, one-size-fits-all policies. Standardised lockdowns, mask mandates, and testing policies worked in some places but backfired in others. Countries that allowed local health authorities to adjust strategies had better long-term results.

As with issues of public health, educational interventions should balance standardisation with adaptability, ensuring coherence without rigid uniformity.

From Brutalism to biomimicry?

If schools are complex, adaptive systems, then trust leadership must reflect that reality. The challenge is that many of our prevailing models of trust leadership and their associated management theories are built on assumptions of predictability and control—on the idea that standardisation, hierarchy, and top-down management can secure better outcomes. But as we’ve seen, schools don’t work like that.

They are interdependent—what happens in one part of the system affects the whole.

They are constantly adapting—leaders and teachers respond dynamically to new information.

They are emergent—some of the best ideas don’t come from the centre; they evolve from practice.

And they resist over-standardisation—what works well in one school might not work in another.

If trust leadership is to be fit for purpose, it can’t just borrow from traditional management models designed for stable, linear environments. It needs an approach built for complexity—one that values coherence over compliance, enablement over control, and adaptability over rigidity.

If the Brutalist vision of school leadership is one of rigid structures, imposed order, and master-planned efficiency, then perhaps it’s time to look elsewhere for inspiration.

Enter biomimicry—a school of design that looks to nature for solutions. Instead of forcing top-down control, biomimicry embraces adaptability, decentralisation, and resilience. It sees structure not as a rigid blueprint but as an evolving framework, where forms emerge in response to real-world conditions rather than being imposed from above.

Architects working in biophilic and biomimetic design don’t just design buildings—they design environments that interact with their users. Structures breathe, evolve, and respond to the ecosystems around them.

What if we designed trusts that worked in the same way? What if leadership structures were more like self-regulating forests than centrally planned cities—allowing schools to adapt, evolve, and thrive in response to their context?

We might have to park this metaphor here but that’s the focus of the next article in this series! We’ll explore:

Why traditional management models—built for predictable systems—don’t fit the reality of schools;

What trust leadership can learn from sectors that manage complexity well; and,

The shift from ‘command-and-control’ leadership to models that enable local adaptation.

If schools are complex systems, then trust leadership must evolve.

Let’s embrace and design for complexity.