Re-designing school trusts from first principles

Deliberately structured to remove friction, unlock potential, and make it easier for the people closest to children to do their best work.

In Soccernomics, Simon Kuper and Stefan Szymanski examine why so many football managers are former players. Their argument isn’t that playing experience is irrelevant—far from it—but they point out that the skills required to excel on the pitch are very different from those required to lead a team from the sidelines.

Yet, the world of football long assumed that playing experience was the best (or only) route into management. Kuper and Szymanski argued that this assumption was self-reinforcing: clubs tended to hire former players, so alternative pathways rarely emerged. As a result, the game has historically overlooked individuals who, while lacking elite playing experience, may have the strategic, analytical, and leadership skills required to manage a modern football team successfully.

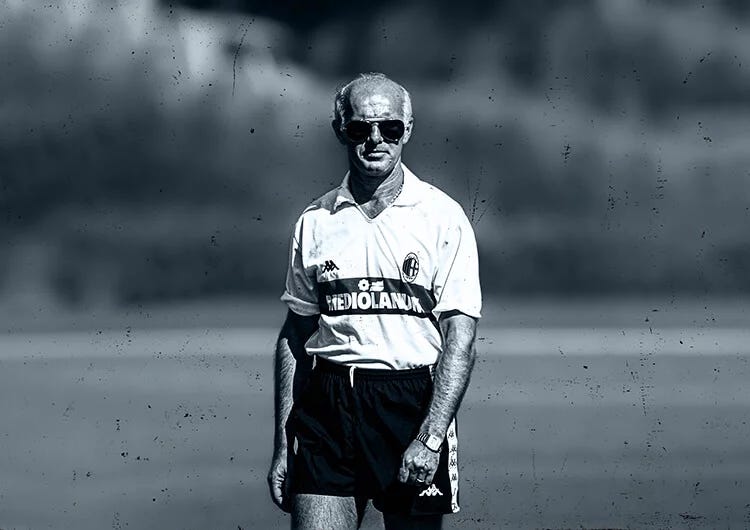

Arrigo Sacchi—the shoe salesman turned iconic football manager—illustrated the point with a playful analogy:

‘You don’t need to have been a horse to be a jockey.’

However, in recent years, this pattern has started to shift in football. Some of the most innovative and successful managers today—Klopp, Tuchel, Nagelsmann and friends—did not have top-level playing careers. Instead, they built their expertise through coaching, analysis, and leadership development. Not only has their success challenged long-held assumptions about who is best placed to lead and what skills and experiences they need to thrive—but it’s significantly impacted the structures put in place to best support clubs’ football programmes.

I would argue that education, in the early throes of academisation, at least, has fallen into a similar pattern. While the nature of the challenge is different, the underlying dynamic is the same. The leadership of school trusts is dominated by educational expertise. In many respects, this is entirely understandable—the ‘trust system’ is still relatively immature and deep experience in schools provides vital insight into their day-to-day realities. We simply couldn’t function without it.

But running a trust is not the same as running a school. The domain-specific expertise required to run a trust effectively is far broader than ‘education’. It requires fluency in organisational strategy, finance, operational scaling, workforce development, business development, governance, partnerships, and change management—expertise that must be integrated into a leadership model that blends educational, operational, and entrepreneurial leadership. Greany & Kamp (2022) have interrogated how school networks operate in England and New Zealand. Their findings reinforce the idea that leading a network of schools requires a different skill set than leading a single school—one that balances systems thinking, facilitative leadership, and strategic governance.

In this article, I want to explore how trust leadership could evolve to meet the complexity of schools; moving beyond rigid, efficiency-driven models towards structures that add real strategic value. If trusts are to deliver on their potential, they cannot simply be scaled-up versions of schools. Instead, they must become intentionally designed organisations that enable schools to achieve more than they could on their own. And that requires a shift in how we think about and structure trust leadership.

From gatekeeping to groundbreaking

The role of a school leader is to lead a school. The role of a trust leader is to lead a trust. These are two very different jobs. For a long time, the view that trust CEOs must have deep educational expertise has been widely held. As in football, that view is softening. And while I’m encouraged by this, I think we need to take another step back to look at the bigger picture; we need to think more critically, and creatively, about the role of the trust and structures required to enable it. This is an invitation to grow.

To their credit, the NPQ frameworks acknowledge the distinction between sector expertise and organisational leadership. They reflect a more sophisticated view of system leadership, drawing on principles of transformational, distributed, and systems leadership. The NPQEL framework, in particular, recognises that the role of a trust leader is not simply to scale school leadership but to create the conditions for collective success across a network of schools.

However, in practice, this nuance has not yet become the norm across the piste. While some trust structures reflect a centralised, efficiency-driven model, where trust leadership is focused on ensuring fidelity to a prescribed model to ‘raise the floor’; others have adopted a highly decentralised approach, where schools operate with significant autonomy but without a clear strategic framework to ensure coherence and shared purpose across the network.

Both of these approaches have their benefits: greater consistency is a key lever of improvement; autonomy can unlock energy, creativity, and responsiveness at the local level. But neither approach, on its own, is enough.

One risks flattening professional judgment and stifling innovation; the other risks fragmentation, duplication, and drift. What’s missing in both cases is intentional design—a structure that enables adaptation without chaos, coherence without control.

If schools are complex systems, then trusts must act less like machines and more like ecosystems: enabling, resourcing, and connecting, rather than directing, duplicating, or retreating.

That shift requires a new model—one that balances autonomy with alignment, and makes it easier for great things to happen in every school, without needing to happen in the same way. A high-performing trust should:

Reduce friction. It should focus on alleviating the administrative and operational burdens that consume school leaders’ time.

Amplify expertise. It should provide rapid access to high-quality, specialist functions (SEND, CPD, branding, finance, communications) that a single school would struggle to sustain alone.

Deploy resources nimbly and responsively. It should ensure that knowledge, funding, and capacity are directed where it will have the greatest impact towards accomplishing the trust’s mission.

The goal is not to make every school the same but to enable every school to be better—by freeing up school leaders to focus on what matters most: teaching, learning, and building relationships.

A blueprint for change

If school trusts are to move beyond scaling school leadership, they need to be designed differently. This is not about minor adjustments—it’s about fundamentally rethinking what a school trust is and does.

1️⃣ From control to enablement

Instead of scaling up school leadership, trusts should be designed as strategic enablers. Trust leadership should be balanced between three complementary domains:

Educational leadership—focused on curriculum, pedagogy, and professional development. Leaning into Bauckman & Cruddas’ theorisation that trusts are ‘knowledge-building institutions’, this function would be less focused on individual school improvement and more focused on trust/network and, indeed, sector development.

Operational leadership—that is, finance, HR, estates, digital transformation, and compliance.

Strategic leadership—responsible for system design, long-term planning, strategic communications and external partnerships.

Decision-making should be distributed rather than centralised. Instead of dictating every detail of school operations, principally, schools should retain autonomy within a structured framework.

Trusts should introduce ‘Enablement Teams’ to bridge the gap between ‘trust’ and ‘school’ leadership functions. That is, a new type of function within ‘the central team’, to ensure that: (i) school leaders receive meaningful, needs-driven support (rather than top-down mandates), and (ii) trust leaders can focus on long-term, strategic objectives.

In the parlance of complexity science, these Enablement Teams would provide a new ‘modularity’—a semi-autonomous, interdependent function. They would:

Broker and coordinate support. Ensuring that schools can quickly access high-quality support, rather than struggling with fragmented services.

Add capacity. To both schools and the trust. They’d provide additional capacity to schools directly in the short-term, and build it in the long. I’m thinking of expertise like school improvement, SEND support, workforce development, etc.

Resource deployment. The Enablement Team would alleviate the operational from trust leadership by using real-time data and school feedback to allocate resources where they will have the most impact.

Empower school-led, local problem-solving. Maybe this is more of an approach or a mindset than a function, per se, but the Enablement Team would work alongside schools to tailor approaches to local needs. Less ‘monitoring’ and ‘directing’, more coaching and empowering.

2️⃣ From compliance to emergence

Too often, trust governance focuses too narrowly on compliance and risk management, reducing boards to oversight bodies that monitor rigid metrics rather than shaping the long-term direction of the trust. While accountability is essential, governance that is overly focused on assurance rather than strategic enablement can leave trusts operating in a way that is technically compliant but strategically stagnant.

What doesn’t work: Compliance-driven boards monitoring performance metrics in isolation, reinforcing a transactional relationship between governance and executive leadership. This is limiting.

What’s needed: Governance that provides long-term strategic direction, ensuring the trust is designed to evolve, learn, and adapt while maintaining coherence across schools.

CST’s Next-gen governance report highlights that while trusts are generally strong in regulatory compliance, many boards lack confidence in strategy and leadership. This compliance-first mindset can lead to fragmented governance, where oversight is reduced to performance monitoring rather than fostering a shared sense of purpose and long-term ambition.

Governance must allow for emergence, not just control. Governance must be designed not just for accountability but for adaptability too—enabling school trusts to evolve, share knowledge, and iterate on strategy rather than simply enforcing static policies. In a well-designed organisation, governance is not a barrier to innovation—it is a foundation for it.

If we get this right…

Why does any of this matter? Education reform is rarely about the present—it’s about shaping the future. The way we design trusts today will define how schools function for decades to come. But this isn’t just a debate about leadership structures or governance models. None of this matters if it doesn’t fundamentally improve the experiences and outcomes of children.

We stand at a crossroads. We can continue tweaking our inherited model, making incremental adjustments to a system that was never designed with scale in mind. Or we can choose to build something better—something that doesn’t just replicate school leadership at scale but redefines what it means to lead an educational system. This means making deliberate choices about the kind of structures we put in place.

Do we want to build trusts that strengthen school leadership—or ones that override it?

Do we want to design governance to encourage innovation—or to police compliance?

Do we want to enable schools to solve problems—or insist that solutions only come from the top?

These are not abstract organisational questions—they determine whether a child walks into a school where teachers feel empowered, well-supported, and focused on their students, or one where leadership is distracted by bureaucracy, compliance, and operational constraints. Ultimately, they determine whether a struggling child receives the right support at the right time or gets lost in a system.

If we get this right, trust leadership will no longer be about command-and-control structures, rigid policies, or drives towards uniformity. It will be about creating the conditions for schools to thrive—by removing friction, amplifying expertise, and strategically deploying resources where they matter most.

The challenge now is not just whether we can imagine a better future for trust leadership—but whether we are willing to build it. Because the structures we create today won’t just shape the experience of school leaders—they will determine the opportunities available to the children they serve. If we get this right, we won’t just be leading trusts—we’ll be shaping the future of education itself.